In early February 1897 fighting was taking place throughout Crete between Insurgents and regular and irregular Ottoman forces, Greek volunteers from the mainland were still arriving on the island, and two Greek naval flotillas were en-route. One of them was to land troops under Colonel Vassos at Platanias, the other, the sloop Sphacteria accompanied by four torpedo-boats, the latter under the command of Prince George of Greece, was bound for Canea.

The European Powers, which already had their warships in Crete had, by this time and after much deliberation and many complaints and threats of war from the Porte, agreed a response should matters escalate. Although a formal blockade of the island was not yet in force and wouldn’t commence until 21 March,[1] upon the appearance of Greek warships, the Powers determined to prevent Greek aggression in Crete, by the use of force if necessary.[2] On 12th February 1897 Rear- Admiral Harris, Senior British naval Officer, was informed:

“Admiralty telegraph that you should concert with the naval Commanders of the other Powers in the event of need, for the prevention of any aggressive action on the part of Greek ships of war which have been despatched to Crete, and in general for the adoption of any measures which the circumstances may render expedient. Act accordingly, and report fully by telegraph action taken or about to be taken.”[3]

The stance of the French Navy was confirmed the following day, the Admiralty informing Harris that the French Admiral had the authority ‘to oppose by combined action, if necessary, and after employing all the means of persuasion and intimidation in their power, an aggressive action by the Greek ships of war’ and ‘the agreement between the commanders should be recorded in writing.’[4]

While the political decisions had been taken in the European capitals, in Crete, matters were coming to a head. In response to the disturbances on the east of the island, the Ottoman authorities attempted, on the 12th of February, to reinforce the garrison at Sitia by sending troops from Candia on board the lightly armed despatch vessel Foud. This troop movement was intercepted within Cretan waters by the Greek unprotected Cruiser Admiral Miaulis which opened fire on the Foud, preventing her from landing her troops and forcing her to return to Candia.

The British magazine The Graphic, reported the incident on 27th February as follows:

Miaulis firing on Faoud. Graphic 27 February 1897

‘A British naval officer, describing the firing of the first shot in the present crisis by the Greek warship Miaulis, which attacked a Turkish despatch boat on the 12th inst., says:- “The Turkish despatch boat arrived here on the 11th, and on the 12th took troops on board and weighed anchor. However, the Greek warship was before her, and was already under way with top-gallant masts housed…. The Turk steered along the coast of Crete with the Greek about half a mile astern of her. Matters proceeded thus until the Turk stopped off Sitia (about fifty miles east of Candia), and attempted to land her troops. As soon as the Greek saw this she fired a gun across her bows, and two more, which went over her. The Turk, evidentially thinking that discretion was the better part of valour, embarked her men again and came back here, where she anchored, but she still has her troops on board.’[5]

The incident had almost immediate consequences. On hearing of it, Sir Alfred Biliotti, British Consul on Crete, sent an urgent telegraph to the Foreign Office at 8 a.m. on 13th February:

‘I have just heard from the Vali that the Turkish steam yacht “Fuad” sailed for Sitia, having on board one company of soldiers and one of gendarmes. Greek iron-clad followed it as it left Candia, and fired on it and compelled it to put back. The Mussulmans are greatly excited, and unless the steam-yacht can leave Candia tomorrow for its destination in safety the most serious consequences may ensue.’[6]

The Foreign Office’s response was swift. By 12.40 p.m. that day, Lord Salisbury, the British Foreign Minister, set in motion instructions to the Royal Navy Commanders on the spot to “inform the Greek naval Commander that, as no declaration of war has been made, the will not be allowed to open fire upon Turkish ships in Cretan waters” and asked the other Powers present to instruct their Naval forces to do likewise.[7]

Although the date of the reaction isn’t made clear, it was either the 12th or the 13th of February, shortly after the Miaulis fired on the Fuad, the Royal Navy took steps to intervene:

‘Captain Grenfell, of Her Majesty’s Ship “Trafalgar”, stationed at Candia, strongly remonstrated with the Captain of the “Miaulis” for this breach of international law and received his parole not to repeat the offense.’[8]

By 14th February the Fuad had arrived off Canea where, by now, Prince George and his ships had arrived. The arrival in Canea of the Fuad, which, as an Ottoman vessel in the waters of an Ottoman island, was perfectly entitled to be there, produced an unfavourable reaction from the Greek vessels. According to British accounts, the torpedo-boats in the company of the Sphacteria appeared to behave in a manner which threatened the Ottoman steam-yacht. In response to the torpedo-boats’ actions, the British and European warships cleared for action and prepared to fire on the Greek vessels.

The Watchers watched.

“A Turkish troopship arrived off Canea on the 14th, and almost directly afterwards a Greek cruiser, with Prince George of Greece on board, in company with four torpedo-boats, came up. The torpedo-boats hovered stealthily about the anchorage, closely watched by the British and foreign warships, which cleared to fire on the Greek scouts if necessary. The Turkish transport got underway as soon as possible and proceeded to Suda.”

Fortunately for Prince George and the Greek Navy, there being no possibility whatsoever of the out-fighting the forces of the European Powers, the incident came to nothing. Rear-Admiral Harris reported:

‘The Captain of the Sphacteria and Prince George paid an official visit to me and made no secret of their intention to acts of hostility with a view to an insurrection in favour of replacing the Turkish by the Greek Government. They seemed greatly disappointed and disquieted when I informed them of my orders to prevent any aggressive action’.[9]

Shortly after this, the Greek warships departed Crete and returned to Greece. However, if the author of an article in the Graphic is to be believed, the Sphacteria was still in Cretan waters on 19 February and made a further attempt to interdict an Ottoman vessel.

Sissoi Veliky intercepting Sphacteria. Supplement to The Graphic, 6 March 1897.

“On the morning of February 19 a Turkish transport, with only a few wounded men on board, left Canea for the westward. The Greek corvette Sfaktirea (sic) suddenly steamed out and tried to intercept her. The Turk immediately altered her course man-of-war towards where the fleet of foreign warships were lying. The Russian man-of-war Sissoi Veikey (sic) was at once despatched to her assistance and conveyed her clear of the island, the Greek corvette retired.”

The Foud [alt. Fauod, Fauot] was a British build steam Despatch vessel. Laid down in Milwall, south London, in 1884, she was launched in 1885. In 1908 she was a stationary hulk in Thessaloniki, used as a hospital ship. There she was captured by the Greeks in November 1912. According to one account, upon capture,she was taken into the Greek Navy before being returned to Turkey in 1919 and eventually scrapped in 1921.[10]

Ottoman Despatch vessel Fuod/Fauod.

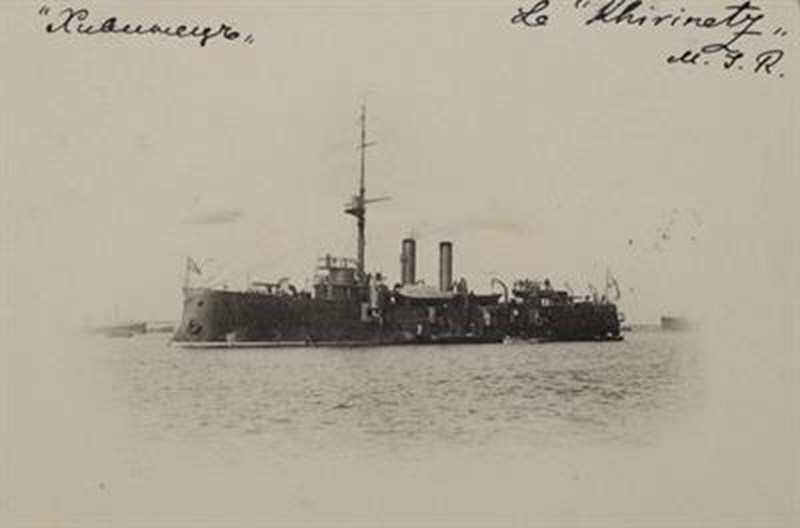

The Admiral Miaulis [Ναυαρχος Μιαουλης] was an iron-hulled, barque-rigged unprotected Cruiser, laid down in France in 1878 and launched in 1879. In 1900 she made history by being the first ship in the Greek Navy to make an official visit to the United States of America.[11] She became a gunnery training hulk in 1912 and was eventually scrapped in 1931.[12]

Admiral Miaoulis-1897

Admiral Miaoulis 1900.

Admiral Maioulis in Valetta 1904.

[1] [C8437] Turkey No.10 (1897) Further Correspondence respecting the affairs in Crete (In continuation of “Turkey No.8 (1897)” and in completion of “Turkey No.9 (1897)”. No.291 Harris to Admiralty, 18 March 1897.

[2] [C. 8664] Turkey. No. 11 (1897). Correspondence respecting the affairs of Crete and the war between Turkey and Greece. [Hereafter: Turkey No. 11, 1897.] No. 74. Monson to Salisbury, 13 February 1897

[3] [C8429] Turkey No. 9, 1897. Reports on the situation in Crete. [Hereafter Turkey No.9, 1897.] No. 1 Rear-Admiral Harris to Admiralty 24 February 1897.

[4] Turkey No. 11, 1897. No. 92. Admiralty to Harris, 13 February 1897.

[5] Supplement to Graphic 27 February 1897.

[6] Turkey No. 11, 1897. No. 73. Included in Salisbury to Sir E Monson, Ambassador to Paris, 13 February 1897.

[7] Turkey No. 11, 1897. No. 73. Salisbury to Sir E Monson, Ambassador to Paris, 13 February 1897.

[8] Turkey No. 9, 1897. No. 1 Rear-Admiral Harris to Admiralty 24 February 1897.

[9] Turkey No. 9, 1897. No. 1 Rear-Admiral Harris to Admiralty 24 February 1897.

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_patrol_vessels_of_the_Ottoman_steam_navy#Fuad

[11] http://www.navypedia.org/ships/greece/gr_cr_navarchos_miaoulis.htm

[12] http://www.navypedia.org/ships/greece/gr_cr_navarchos_miaoulis.htm